Symptomatic Treatments

Spasticity is the presence of increased muscle tone or hypertonia, caused by a lesion of the upper motor neurones which can cause muscle stiffness, spasms and pain. Persistently raised muscle tone can result in abnormal posturing of body parts which if prolonged can result in muscle and tendon shortening, fixed deformities and ultimately contractures36. Contractures are characterized by permanent reductions in the range of motion of joints and resistance to passive stretch. This is mediated by neural factors, principally spasticity, and non-neural factors such as structural changes in soft tissues37. Spasms are sudden, involuntary and often painful muscle contractions which are often associated with spasticity and provoked by muscle stretch or other stimuli36. They may be transient or prolonged.

From a pathophysiological point of view, spasticity has been defined as a velocity-dependent increase in tonic stretch reflexes with exaggerated tendon jerks, resulting from hyper-excitability of the muscle stretch reflex38. More recently, the influence of afferent pathways on spasticity has been appreciated so that it may be thought of as a condition of disordered sensorimotor control presenting with intermittent or sustained involuntary activation of muscles39. This is important, since a first step in the treatment of spasticity may be the reduction or elimination of increased afferent input such as that caused by pain, infection, diarrhoea, constipation, urinary retention, tight clothing or poor posture.

Ataxia and spasticity may coexist in a large number of congenital, genetic or acquired conditions including common conditions such as stroke, multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy and head injury. Spasticity is prominent at presentation in some cases of the following conditions and these are sometimes referred to as spastic ataxias40.

- Late-onset Friedreich’s ataxia (LOFA)

- Autosomal recessive Spastic Ataxia of Charlevoix-Saguenay (ARSACS)

- Hereditary spastic paraplegia type 7 (HSP7)

- Adult-onset Alexander disease

- Spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 (SCA3; Machado-Joseph disease)

- Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis

- Fatty acid hydroxylase-associated neurodegeneration

Spasticity has also been described more rarely in a range of other autosomal recessive ataxias, spastic paraplegias and autosomal dominant ataxias including SCAs 1–3, 6–8, 10–12, 17, 23, 28, 30, and 35.

Metabolic causes include:

- Ataxia with Vitamin E deficiency

- Ataxia with Coenzyme Q10 deficiency

- Abetalipoproteinaemia

- Metachromatic leukodystrophy

- Adrenomyeloneuropathy

- Vanishing white matter leukodystrophy

- Krabbe disease

- Gaucher’s disease type III

- 3-methylglutaconic acidaemia type III

- Non-ketotic hyperglycinaemia

- GM2 gangliosidosis40.

Spasticity can affect many parts of the body contributing to a range of symptoms seen in progressive ataxia including dysarthria and dysphagia as well as limb problems such as clumsiness, lack of manual dexterity and difficulty with walking.

Treatment of spasticity

The purpose of treating spasticity is to optimize mobility, standing capacity and upper limb function; to reduce symptoms of pain and spasms, especially those at night which impair sleep and contribute to daytime fatigue; to improve transferring, sitting posture, washing and dressing, and so promote independence and reduce carer reliance; to prevent skin ulceration and the formation of pressure sores; and to prevent contractures and so reduce the development of chronic disability. Treatments may be non-pharmacological (therapy-based), pharmacological or surgical, usually proceeding from one to the next in that order if the previous has failed or provided incomplete benefit.

It is vital that pharmacological and surgical techniques are used in association with patient education and timely physiotherapy to maximize efficacy and maintain benefit.

Non-pharmacological therapies

Physiotherapy has a vital role to play in educating patients and carers in correct posture, muscle use and the avoidance of spasticity triggers such as pain and infection.

Pharmacological Treatments

Although there is little evidence of the efficacy of anti-spasticity interventions specifically in cases of spastic ataxia, a greater evidence base exists in commoner conditions causing spasticity, particularly stroke, multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy, head injury and spinal injury. Since the underlying neurophysiological mechanisms generating spasticity and spasms are similar, treatment decisions have to be made pragmatically by extrapolation of such evidence and on the basis of expert experience. Cochrane Reviews describing the management of spasticity exist for multiple sclerosis41,42, cerebral palsy43,44, spinal cord injury45 and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis46.

Most clinicians start with the following oral medications for generalised spasticity (usually in this order due to the profile of side effects and better tolerability): baclofen, tizanidine, gabapentin, clonazepam, dantrolene sodium or diazepam. It is advisable to start at a low dose for all medications and increase the dose slowly. Chronic use of diazepam is not recommended apart from in very severe cases. If these are not successful or not tolerated, greater CNS concentrations of baclofen can be achieved with reduced peripheral exposure to side effects by the use of an intrathecal baclofen infusion, although this requires careful patient selection, planning and an expert centre to undertake the procedure and follow-up47.

Many other oral medications have shown some evidence as anti-spasticity agents including methocarbamol, levetiracetam, lamotrigine, pregabalin, progabide, clonidine, piracetam, vigabatrin, prazepam, cyproheptidine, L-threonine, thymoxamine, orphenadrine and 3,4-diaminopyridine. However, these are rarely used in practice. Intrathecal phenol has also been used but because of the destructive nature of the agent, its use is restricted to those patients with severe lower limb spasticity who cannot be managed by alternative means36.

Anecdotally, it is known that patients with ataxia sometimes gain benefit from the use of cannabis products in reducing pain and spasticity. Studies of Cannabis sativa extract and synthetic cannabinoids in MS and other neurological conditions have shown significant reductions in pain, spasms and spasticity48. However, the largest of these trials49,50 failed to show significant reductions in objective markers of spasticity, so further research is required.

In all cases, there can be paradoxical worsening of mobility or other functions by unmasking of underlying weakness51. Patients should therefore be warned of this possibility beforehand. In addition, it highlights the importance of titrating the dosage of medications slowly in order to avoid this, and the medication should be stopped or reduced if worsening of mobility or other functions occurs.

Focal spasticity, particularly in small muscles, is probably best treated with intramuscular botulinum toxin injections for which numerous well-controlled, randomized trials have shown benefit52. It is advisable to be referred to a specialised clinic for such treatment. There is evidence that this benefit is prolonged by adjunctive therapies such as stretching, taping, casting, dynamic orthoses or electrical muscle stimulation. It is therefore very important that such injections are accompanied by a course of physical therapy at the time or immediately after injection.

Spasticity can be associated with painful nocturnal cramps. In the elderly, quinine sulphate has been used extensively to try and alleviate this. However, it has been associated with serious adverse events (particularly cardiac ones) and so its use is not generally recommended for patients with cardiac conditions and for patients with Friedreich’s ataxia.

Surgical Treatments

Surgical treatments are generally considered options to be taken only when physical and pharmacological interventions have not worked. However, they may be considered in exceptional cases, particularly in the case of fixed, non-reducible deformities or where ablation of specific nerve fibres will result in improvement in a specific focal symptom. Surgical treatments include orthopaedic procedures such as tendon lengthening, tenotomy or tendon transfer; and neurosurgical procedures such as peripheral neurotomies, dorsal rhizotomies and microsurgical ablation of the dorsal root entry zone (‘DREZotomy’)53.

| Recommendations | Grade | |

|

1. |

Careful assessment by a neurologist, with advice from a physiotherapist, is required to decide on the type of treatment of spasticity. |

GPP |

|

2. |

Consider physiotherapy first to treat spasticity, and if that does not provide complete benefit use pharmacological treatment. Surgery should be considered in cases where physiotherapy and pharmacological treatments have not worked. |

GPP |

|

3. |

For pharmacological treatment of generalised spasticity consider using the following oral medications (usually in this order due to the profile of side effects and better tolerability): baclofen, tizanidine, gabapentin, clonazepam, dantrolene sodium or diazepam. |

GPP |

|

4. |

To treat focal spasticity, particularly in small muscles, refer to a specialised clinic for treatment with intramuscular botulinum toxin injections, followed by physiotherapy. |

GPP |

Tremor can be an intrusive complaint in some patients with ataxia, and is classically described as being of “intention” type (with the amplitude of shaking increasing as the target is approached). “Maintained posture” tremor can also be encountered. Although tremor is especially notable in Fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome and SCA12, it can be present in virtually any form of progressive ataxia. The copresence of sensory disturbance (and especially joint position loss) can further exacerbate tremor.

Treatment is difficult, and the variety of pharmacologically unrelated agents promoted as potential therapies is a testament to their general lack of efficacy. The published data up to 2005 have been reviewed54. Generally speaking, good quality randomised controlled trial data for the use of any of the agents suggested in the management of cerebellar tremor is lacking. A conventional approach to the medical management of tremor in ataxia is shown in table 9.

Table 9: Pharmacological treatment of tremors in patients with progressive ataxia (listed in the order of general usage)

| Drug | Starting dose (daily) | Usual maintenance dose |

|

Propranolol |

20mg |

80—160mg daily (using a long-acting formulation) |

|

Primidone* |

50mg |

125—250mg twice daily |

| Propranolol and Primidone combined | ||

|

Topiramate* |

12.5mg |

25mg twice daily |

|

Clonazepam |

0.5mg |

0.5mg |

|

Gabapentin |

200mg |

400—800mg three times a day |

*Additional caution to be exercised in the elderly with the use of these medications for possible side effects.

Physiotherapy may be helpful in the management of tremors and should be considered (see section Physiotherapy).

In patients where tremor is extremely debilitating and not responsive to medication, a referral to a centre specialising in functional neurosurgery should be considered.

This is because there may be a useful role for functional neurosurgery, including deep brain stimulation (DBS), in the management of tremor, although here too studies specifically for the management of cerebellar tremor are lacking. In a study of a patient with SCA2, chronic thalamic stimulation was shown to improve severe resting and action tremor55. Improvement in unilateral cerebellar tremor in a single subject has been described after Vim (nucleus ventralis intermedius) and latterly PSA (posterior subthalamic area) DBS56. Benefit has also been reported from the use of DBS (of Vim) in a single subject with abetalipoproteinemia57, and in FXTAS20.

For information on dystonic tremor see subsection below.

| Recommendations | Grade | |

|

1. |

Patients with ataxia who have tremors should be offered pharmacological treatment using the drugs described in table 9 to be tried in the order they are listed until symptom relief is achieved. |

GPP |

|

2. |

In patients where tremor is extremely debilitating and not responsive to medication a referral to a centre specialising in functional neurosurgery should be considered. |

D |

Dystonia is characterised by sustained co-contractions of agonist and antagonist muscle groups in different parts of the body, resulting in abnormal postures and twisting/repetitive movements, and can be focal, segmental or generalised. Dystonia can be an accompanying feature of many ataxic conditions. Patients with ataxia who develop dystonia most commonly have a focal form of dystonia. An “idiopathic” form characterised by predominantly (focal) cervical dystonia and ataxia has been reviewed58. Even this clinically relatively homogeneous entity is thought to be aetiologically heterogeneous.

A number of treatment options for dystonia, including oral drugs, botulinum toxin injections, surgical techniques (globus pallidus interna stimulation) and physiotherapy are available. Oral drugs are unfortunately often ineffective. The first treatment option for focal dystonia is botulinum toxin injections. For generalised dystonia, a trial of oral medications should be offered first, followed by surgery if this is not successful.

In patients with dystonic tremor, physiotherapy and pharmacological intervention with drugs such as trihexyphenidyl and orphenadrine should be the first treatment options, followed by surgery if these are ineffective. A number of reviews of the treatment of dystonia are available, and these strategies can be adapted in the management of this complication in patients with ataxia59–61.

| Recommendations | Grade | |

|

1. |

Focal dystonia should be treated with botulinum toxin injections. |

GPP |

|

2. |

Generalised dystonia should be treated with oral medications, followed by surgery if this is not effective. |

GPP |

|

3. |

Patients with dystonic tremor should be offered physiotherapy and oral medications followed by surgery if the former are ineffective. |

GPP |

Scoliosis is derived from the Greek word ‘Scolios’ meaning crooked. It is the lateral curvature of the spine associated with twisting of bony elements (vertebrae) along with deformation of chest cage producing ‘rib hump’ deformity. If left untreated, the scoliosis may progress with time and cause rigid ‘C’ or ‘S’ shaped curvature of the back with compression of lungs and other internal organs resulting in severe pain with shortness of breath. It may also result in having difficulties with sitting properly in a wheelchair due to pelvic obliquity (ie: tilting of the pelvis).

Scoliosis is a common feature in people with Friedreich’s ataxia; with up to 60% developing spinal deformity (scoliosis/kypho-scoliosis)62. If left untreated, this may become severe with time due to the underlying progressive neurodegenerative disorder and worsening of spinal deformity with growth62–65. It is therefore important for neurologists and paediatricians to carry out an evaluation of the spine and regularly monitor the potential development of scoliosis in Friedreich’s ataxia patients, especially in children.

If scoliosis is detected, referral to a spinal surgeon is recommended. The urgency of referral is determined by severity of curvature and co-existent pain/discomfort.

Spinal assessment: On referral to a spinal unit, patients are seen by a specialist spinal deformity surgeon who will request an x-ray of the whole spine (standing or sitting) to determine the magnitude/severity of spinal curvature. This measurement (Cobb angle) is recorded and overall spinal balance in both frontal (ie: coronal) and sideward (ie: sagittal) planes is evaluated. A detailed neurological assessment is also undertaken and findings documented. An assessment of posture and seating ability (in wheelchair users) along with degree of constriction of rib cage by pelvis (costo-pelvic impingement) is determined64–66.

Treatment: If scoliosis is diagnosed a referral to a physiotherapist to advise on posture and exercises is recommended. For mild deformities, the curvature is kept under close observation and the spinal surgeon may discuss bracing (i.e. a rigid plastic corset is worn like a garment)65,66. The brace holds the spine straight by three-point contact pushing on muscles and correcting the spinal curvature. It is important to follow the advice of the specialist spinal surgeon and for the patient to wear the brace diligently as advised64,65.

For severe deformities, the surgeon may discuss the need for an operation and explain the risks/benefit of surgery in greater detail62,67. Further special investigations may be requested to thoroughly evaluate patient(s) prior to surgery. These investigations may include:

- CT Scan

- MRI Scan

- Cardiac ECHO: Assessment of cardiac function

- PFT: Pulmonary (ie: lung) function tests

- Sleep studies

Surgery: The operation may involve one or two surgeries to straighten the spine and hold it in corrected position by using rods, screws and wires62,65. These implants act as scaffolds holding the spine straight until the bony elements knit together (fusion occurs). One would be several inches taller after the operation and anticipated stay in hospital is likely to be a few weeks. The anticipated time to recover from surgery is likely to be a few weeks to a couple of months. The outcome of the surgery can be rewarding for the patient with improved quality of life and seating ability in a wheelchair, and reduction in pain62,67. Liaison between the surgeon, anaesthetist and cardiologist is important when surgery is planned, and careful consideration should be given to fluid management and monitoring during surgery. This is particularly relevant if patients with Friedreich’s ataxia already have cardiac problems.

Further follow-up and continuity of care: The rods/implants will stay inside the body for the rest of the person’s life and it is important for the surgeon to continue to see the patient regularly in out-patient follow-up clinics every few months for the first year and every 6–12 months after the first year. Serial x-rays of the whole spine are done at each visit and assessed for progression to bony union / fusion. Life-long follow-up may be needed to ensure there are no untoward events (rod breakage/screw backout which may happen infrequently)62,67.

Complications: Any concerns from the patients with surgical wounds or any other issues should be discussed with the GP initially. On evaluation the GP would arrange a referral to a specialist if appropriate.

| Recommendations | Grade | |

|

1. |

Regular surveillance of the development of scoliosis in Friedreich’s ataxia patients (especially children) is recommended as it is important for it to be treated. |

GPP |

|

2. |

If scoliosis is detected, referral to a physiotherapist and spinal surgeon is recommended. |

GPP |

|

3. |

For mild scoliosis the patient should be kept under close observation and the spinal surgeon should consider treatment with bracing. |

B |

|

4. |

For severe scoliosis consider surgery to straighten the spine. |

B |

|

5. |

Regular follow-up by a spinal surgeon is recommended after an operation on the spine. |

B |

Chronic pain in patients with ataxia can arise through musculoskeletal or neuropathic (peripheral and central) causes. It can be a distressing complaint particularly in advanced ataxia, where in addition to neuropathic pain, pain can also arise from joint/spinal deformity and abnormal positioning. A variety of interventions, including physiotherapy, are available for pain management. A number of drugs are available to treat neuropathic pain, with the most commonly used drugs being Amitriptyline, Nortriptyline, Carbamazipine, Pregabalin, Gabapentin and Duloxetine68.

Referral to a pain management clinic may be necessary in some cases, where inter-disciplinary input including physiotherapy and psychological therapies can be used for the management of pain68.

| Recommendations | Grade | |

|

1. |

Treat pain with physiotherapy and/or pharmacological treatments. |

GPP |

|

2. |

Consider use of the following drugs to treat neuropathic pain: Amitriptyline, Nortriptyline, Carbamazipine, Pregabalin, Gabapentin and Duloxetine. |

GPP |

|

3. |

Consider referral to a pain management clinic if pain is severe or limiting daily activities. |

GPP |

Cardiac involvement in Friedreich’s ataxia is frequent, exceeding 90% of the patients in some studies and reports69 (this applies to ECG measures rather than structural/functional changes). It is therefore essential to involve a cardiologist in the screening of patients with Friedreich’s ataxia for the early diagnosis of cardiac problems and the management of cardiac complications where required. A broad clinical spectrum is seen with cardiac pathology.

As in all other cardiomyopathies, increased awareness is paramount for the recognition, diagnosis and management of patients who suffer from these abnormalities. Although the cardiac abnormalities are gradual and progressive and cardiac risk does not appear to precede symptoms, the overlapping aetiologies of their symptoms may justify preventative cardiac screening. Expert opinion would suggest that it would be advisable for patients to be screened once every two years before any cardiac disease is documented, and at least annually after manifesting features of asymptomatic cardiac disease.

Clinical presentation

Friedreich’s ataxia patients report breathlessness, and less frequently chest pain. It is sometimes difficult to discriminate the origin of these symptoms between cardiac or respiratory/neuromuscular origin. They may also report palpitations, which may be non-specific or attributed to atrial arrhythmias.

Specific aspects of the cardiac phenotype seen in Friedreich’s ataxia can be detected by:

- ECG –There is usually evidence of electrocardiographic abnormalities mainly in the form of nonspecific repolarisation changes,70–72 T wave inversion and also deep S-wave in V1 and V2, and high R-wave in V5 and V6 (LVH)72. The QRS and QTc duration are expected to be normal. Conduction abnormalities, which would require intervention are rare73,74.

- Echocardiographic abnormalities – More than 50% of the patients have abnormalities on cardiac imaging75. The typical pattern is concentric left ventricular hypertrophy with an end-diastolic wall thickness in most patients of less than 15 mm, and absence of outflow tract obstruction74,76.

Patients with an earlier diagnosis (and presumably onset) of disease generally also show more severe cardiac involvement76. With time, it is likely that there will be some degree of regression of the hypertrophy in these patients resulting in thinning and dilatation of the left ventricle. This does not represent a variation of the phenotype but rather a progression of the cardiomyopathy. Consequently some patients progress to the dilating phase of the condition and this is associated with severe systolic dysfunction with dilation of the ventricle; it occurs especially at older ages, but is infrequent77.

Diastolic dysfunction is associated with the stage of the condition. There is inadequate volume of data to suggest that there is early or disproportional diastolic dysfunction in patients with FRDA73. A paper has described various clinical features of the FRDA cardiac phenotype but there is no association at present with prognosis and outcome78.

Diagnosis and monitoring

Transthoracic Echocardiography is the method of choice for the diagnosis and monitoring of the myocardial changes. The cardiac MRI as an alternative or complimentary imaging modality has not been widely used so far but it might be helpful to assess the cardiac mass in a more accurate way compared to echocardiography75. It also has the potential to detect areas of expansion of the extracellular volume using Gadolinium imaging which are suggestive of fibrosis in other disease settings.

As part of the cardiac screening it is relevant to test levels of troponin, as a study has shown elevated levels of troponin in 47% of people with Friedreich’s ataxia who did not have active arrhythmia, chest pain or features of acute coronary syndrome at the time of sampling. Although long-term longitudinal studies have not been yet published, it could be helpful to measure levels at baseline for future follow-up of patients and in particular if chest pains occur79.

Cardiac rhythm monitoring – Holter monitors can be helpful for the detection of silent cardiac arrhythmias or the association of symptoms (such as palpitations, shortness of breath) with the underlying rhythm. Arrhythmia is predominantly supraventricular70. The prevalence of atrial fibrillation correlates with the severity of the cardiac disease and therefore has negative prognostic implications76. There is no evidence from the literature that ventricular arrhythmia occurs in early stages or disproportionately to the stage of underlying cardiac condition. Severe arrhythmia is associated with severe dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM)74,80.

Some data suggest an association between electrocardiographic and echocardiographic changes and the size of the GAA expansion in the FRDA gene and the neurologic deficit in Friedreich’s ataxia; however this is not confirmed by all datasets71,74,81–84.

Management

The management of the manifestation of cardiac involvement is symptomatic and also aims to prevent further complications. Depending on the phenotype of patients with Friedreich’s ataxia, guidelines for treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy85 and heart failure86 should be applied and individualised. Although not validated specifically in clinical studies with Friedreich’s ataxia patients, a cardiologist would consider beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors/other vasodilators, spironolactone and loop diuretics for the management of patients who present with heart failure symptoms attributed to myocardial dysfunction. Amiodarone and digitalis have roles in the management of atrial fibrillation; rate control can be achieved also with beta-blockers or calcium antagonists, depending on the clinical circumstances. Treatment may also include implantation of pacing devices with the optional additional capacity of a defibrillator.

An issue which often requires multidisciplinary discussion is the indication and type of anticoagulation for atrial arrhythmias in these patients, who are prone to falls and injury. The decision is usually individualised. The standard treatment is warfarin. The use of the newer novel oral anticoagulants have not been studied in Friedreich’s ataxia, but they may prove a superior option due to the lack of a need for regular monitoring and reduced risk of intracranial hemorrhage.

Cardioverter defibrillator implantation: For all patients, including those with neuromuscular disorders, guidelines on device implantation87 and sudden death prevention should be followed. For individual patients, risks and benefits related to the intervention and its short, medium and long-term consequences should be considered.

Transplantation: Although it is appropriate to consider patients with Friedreich’s ataxia with advanced heart failure for transplantation, the complexity of the underlying condition and multi-organ involvement count as risk factors for a successful transplantation so the patients need to be considered with great caution and on individual basis.

Other drugs: The role of antioxidant agents, such as idebenone and CoQ10 for the treatment of cardiac changes in Friedreich’s ataxia is yet unclear (see section Research).

Standard guidelines for assessing cardiovascular risk factors should be used in all patients and treated accordingly. In the case of statins, despite suggestions that statins lower CoQ10, this should not affect the choice of the treatment of hypercholesterolaemia with statins. Moreover, the number of patients with Friedreich’s ataxia who require treatment with statins is expected to be low in the first four decades of their life.

Conclusion

Although clinical observations and research have offered new insights into the disorder, the natural course of the cardiomyopathy in Friedreich’s ataxia is largely unknown.

Therefore, systematic study and follow-up of patients with Friedreich’s ataxia who exhibit cardiac abnormalities will provide the longitudinal data required to shed light on many aspects of the cardiac manifestation of this disorder, and may help prevent complications and/or delay their progression.

| Recommendations | Grade | |

|

1. |

When Friedreich’s ataxia is diagnosed a referral to a cardiologist is recommended for the early diagnosis of cardiac problems and the management of cardiac complications where required. |

GPP |

|

2. |

Regular screening by a cardiologist is recommended in Friedreich’s ataxia patients; once every two years before any cardiac disease is documented, and at least annually after manifesting features of asymptomatic cardiac disease. |

GPP |

|

3. |

Transthoracic Echocardiography and ECG should be used for the diagnosis and monitoring of the myocardial changes. |

GPP |

|

4. |

Holter monitoring should be undertaken to detect silent cardiac arrhythmias or the association of symptoms (such as palpitations, shortness of breath) with the underlying rhythm. |

GPP |

|

5. |

A cardiologist should consider pharmacological treatment (including the use of anticoagulants), and in some cases the implantation of pacing devices, in collaboration with the neurologist. |

GPP |

From the limited data available, lower urinary tract symptoms appear to be common in people with ataxia. Symptoms occur most prominently in Multiple System Atrophy (MSA), and may even manifest prior to other neurological symptoms88. In Friedreich’s ataxia, a prevalence of 23% was seen in a study of 140 patients89. The most common symptoms relate to problems with storage and include urinary urgency, frequency and incontinence (overactive bladder symptoms). Urodynamics may demonstrate uninhibited detrusor contractions and altered bladder capacity90,91. Problems with voiding may occur as well, especially in multiple system atrophy88 and Spinocerebellar ataxia type 3, and individuals may report urinary hesitancy, poor stream, sensation of incomplete bladder emptying and double voiding, or may be in retention88,92. Incomplete bladder emptying may result in recurrent urinary tract infections.

Diagnostic Approach

Lower urinary tract dysfunction should be managed by a suitably trained healthcare professional who is knowledgeable both about ataxias as well as managing the neurogenic bladder. The post–micturition residual urine should be measured as part of the initial assessment and preferably before antimuscarinic medications are started. This measurement can be made either using ultrasound or in-out catheterization. Urinary tract infections (UTI) may mimic overactive bladder symptoms and can themselves worsen neurological disability. ‘Dipstick’ tests of the urine using reagent strips to test for UTIs should be used to exclude infection. Urodynamics are not routinely performed unless bladder symptoms are refractory to treatment or intravesical treatments are being planned. It is also important for urological/gynaecological causes for lower urinary tract symptoms such as prostate enlargement or stress incontinence to be appropriately ruled out.

Treatment

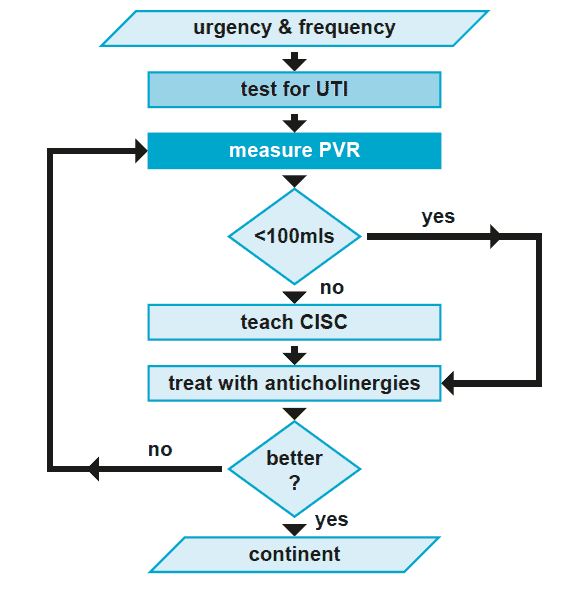

In the majority of cases, the bladder can be successfully managed using a simple algorithm which has been adopted from treatment guidelines for bladder dysfunction in patients with Multiple Sclerosis93 (figure 1). Practical advice should be given about cutting down caffeine, fizzy drinks and alcohol, as well as information about timed voiding and bladder retraining whenever appropriate. The fluid intake should be individualized, particularly taking into consideration possible concurrent cardiac issues; however a fluid intake of between 1 to 2 litres a day is recommended93. Pelvic floor exercises may be helpful especially when symptoms are mild.

Most individuals with overactive bladder symptoms will require antimuscarinic medications (table 10). The most often experienced side-effects are dry mouth and constipation. If the former is too uncomfortable, artificial saliva may be prescribed. Antimuscarinics may increase heart rate, which may be relevant in individuals with cardiomyopathy (eg: in some patients with Friedreich’s ataxia). Cognitive problems can occur in some individuals with ataxia and in the rare situation where cognitive impairment is a feature, antimuscarinics should be prescribed with caution. It would be sensible to use more selectively-acting medications such as trospium or darifenacin. If symptoms continue refractory, intradetrusor injections of botulinum toxin A is likely to be an option, though it remains unlicensed for this indication. More recently, percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation has emerged as an option for managing overactive bladder symptoms.

In individuals with persistently elevated post-void residual volumes in excess of 100 mL, clean intermittent self catheterisation (CISC) is indicated. This should be taught by a urology specialist nurse or continence advisor. Manual dexterity and vision need to be assessed when considering CISC. With advancing disease, a long-term indwelling catheter may be required, preferably suprapubic rather than urethral.

Referral to specialist urology services is indicated in cases of haematuria, suspicion of a concomitant urological condition, eg: prostate enlargement, recurrent urinary tract infections, symptoms refractory to medical management, or for consideration of Botulinum toxin or suprapubic catheterization.

Figure 1.

Algorithm for management of neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction. (UTI – urinary tract infection, PVR – post-void residual volume, CISC – clean intermittent self catheterization).

Table 10: Antimuscarinic medications that can be used to manage overactive bladder symptoms

(reproduced from treatment guidelines for bladder dysfunction in multiple sclerosis)93

| Generic name | Trade Name | Dose (mg) | Frequency |

| Tolterodine tartrate | Detrusitol | 2 | bd |

| Tolterodine tartrate | Detrusitol XL | 4 | od |

| Oxybutynin chloride | Ditropan | 2.5 – 5 | bd – qds |

| Oxybutynin chloride XL | Lyrinel XL | 5 – 30 | od |

| Propiverine hydrochloride | Detrunorm | 15 | od – qds |

| Darifenacin | Emselex | 7.5 – 15 | od |

| Solifenacin | Vesicare | 5 – 10 | od |

| Fesoterodine | Toviaz | 4 – 8 | od |

Legend: od – once daily; bd – twice daily; tds – three times daily; qds – four times daily; XL – extended life.

In addition to the medications listed in table 10, trospium could also be considered as a treatment option, at a dosage of 20mg bd (with reduced dosage in cases of renal impairment) - see treatment section above.

| Recommendations | Grade | |

| 1. | In primary care, test for urinary tract infection and measure PVR (to exclude common causes of urgency and frequency). If these are normal, check for other common causes such as prostate enlargement. | GPP |

| 2. | Practical advice should be given about cutting down caffeine, fizzy drinks and alcohol, as well as information about timed voiding and bladder retraining whenever appropriate. The fluid intake should be individualized; a fluid intake of between 1 to 2 litres a day is recommended (taking into consideration possible concurrent cardiac issues). | GPP |

| 3. | Advice on pelvic floor exercises should be given as it may be helpful especially when symptoms are mild. | GPP |

| 4. | Most individuals with overactive bladder symptoms will require antimuscarinic medications (table 10). | GPP |

| 5. | In patients with cardiac complications and/or cognitive problems caution is advised when using antimuscarinic medications. | GPP |

| 6. | In patients with cognitive problems, more selectively-acting antimuscarinic medications, such as trospium chloride or darifenacin should be considered. | GPP |

| 7. | In some instances referral to an urologist is recommended eg: in cases of haematuria or suspicion of concomitant urological condition. | GPP |

Bowel complications can be present in ataxia as in other chronic conditions. For example, this is well described in Friedreich’s ataxia63. Whilst most commonly presenting as constipation, faecal urgency and incontinence also occur and represent a significant intrusion to quality of life94. Development of faecal urgency and incontinence may be contributed to by other medications, mobility difficulties, age, previous childbirth (especially if forceps deliveries or large babies) and co-existent medical conditions95.

Constipation which does not resolve with lifestyle intervention (diet, fluid and mobility assistance) may need laxatives or suppositories. In patients with faecal soiling, the possibility of severe constipation and overflow incontinence needs to be considered. Urgency and faecal incontinence warrants specialist assessment: treatment options include loperamide, behavioral and pelvic floor directed therapies, and consideration of digital anorectal timulation, depending on specific cause identified at such an assessment. More specific guidance can be found in the NICE guidelines for faecal incontinence in adults95.

| Recommendations | Grade | |

|

1. |

Suggest changes in lifestyle (eg: diet, fluid and mobility assistance) for patients with constipation, followed by the use of laxatives or suppositories. |

GPP |

|

2. |

Consider referral for specialist assessment if patients have urgency and faecal incontinence. |

GPP |

Erectile dysfunction is common and may be the first manifestation of autonomic dysfunction in multiple system atrophy96. Erectile dysfunction can also occur in patients with other ataxias and discussion about sexual function should therefore be included in their consultation. Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors are the mainstay of treatment, eg. sildenafil, tadalafil and vardenafil. Treatment decisions should balance the needs of the person and potential side effects of medications, eg: hypotension. Caution should be exercised in patients with cardiac pathologies (eg: Friedreich’s ataxia), thus a consultation with a cardiologist is advised.

| Recommendations | Grade | |

|

1. |

Consider discussing sexual function with male patients due to the potential for erectile dysfunction. |

GPP |

|

2. |

Treat erectile dysfunction where appropriate with phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors. Treatment decisions should balance the needs of the person and the potential side effect of medications eg: hypotension. |

GPP |

|

3. |

If patients have cardiac pathologies caution should be exercised when considering medication, and consultation with a cardiologist is recommended. |

GPP |

Dysphagia is a common problem seen amongst patients with ataxia, however, it is important for other causes to be excluded. Questions about swallowing difficulties and coughing or choking episodes when eating or drinking should be asked at every clinic appointment. Where symptoms of dysphagia exist, a referral to a speech and language therapist should be made for assessment (see section Speech and language therapy). Difficulties with swallowing may result in a narrowing of the patient’s diet and it is important to strike a balance between providing safe eating/swallowing advice and allowing the enjoyment of food. Significant dysphagia can ultimately result in unintentional weight loss if patients struggle to maintain an adequate caloric intake. High-calorie, nutritional supplements may be of use in these circumstances and early referral to a dietician is recommended. If calorie intake cannot be maintained despite supplements, a discussion about the possibility of a percutaneous gastronomy (PEG) should take place in order to provide a secure means of feeding. This should involve a multidisciplinary team (including a speech and language therapist, dietician and surgeon).

| Recommendations | Grade | |

|

1. |

If patients show symptoms of dysphagia a referral to a speech and language therapist should be made (see section Allied Health Professional Interventions). |

GPP |

|

2. |

If there is unintentional weight loss due to dysphagia consider the use of nutritional supplements and refer to a dietician. |

GPP |

|

3. |

If calorie intake cannot be maintained despite supplements, discuss the possibility of a percutaneous gastronomy (PEG) to provide secure feeding. |

GPP |

It is important for patients with ataxia to maintain a healthy, balanced diet. There are a number of issues that arise in these patient groups that can make this difficult and it is important to discuss these with patients during clinical reviews.

Frequently, patients with ataxia can report issues with weight gain. Whilst the aetiology of this is multifactorial, many patients will report that reduced mobility and an inability to undertake regular exercise is a significant contributing factor. Excessive weight gain can lead to a vicious cycle of deteriorating mobility and it is important therefore to support patients in maintaining a steady weight or in weight management where appropriate. Where possible, facilitated exercise at a gym can be a useful adjunct to dietary measures but this may not be practicable in patients with significant mobility impairment. Diet planning can be facilitated with support from the patient’s GP or community dietician.

It is important that dietary advice be tailored to the individual however there are some general recommendations that can be made. The WHO lists 5 general points that are universally applicable:

- Achieve an energy balance i.e. consume roughly the same number of calories that you burn off through exercise and exertion

- Limit energy intake from saturated to unsaturated fats

- Increase consumption of fruits and vegetables

- Limit the intake of free sugars

- Limit salt intake

Additional advice on a balance diet can be found on the NHS Choices website97.

Specific dietary interventions include the following:

Gluten Ataxia

This is a specific type of ataxia caused by a sensitivity to gluten and there is evidence that a strict glutenfree diet can improve ataxia in these patients (see section Gluten ataxia).

Vitamin E deficiency

Vitamin E deficiency can lead to or exacerbate ataxia. It can be seen as a result of malabsorption (eg: in coeliac disease) or be nutritional, most commonly seen in patients with ataxia due to alcohol. Treatment is with oral vitamin E (100mg daily). There is also a specific inherited form called Ataxia with Vitamin E deficiency in which a higher dose of vitamin E supplementation is required (see section Ataxia with Vitamin E deficiency). Treatment can be difficult in malabsorption syndromes and the underlying causes should be treated where possible. There is no evidence that vitamin E supplementation is effective in ataxia patients with a serum vitamin E level in the normal range.

Ataxia with Coenzyme Q10 deficiency

Ataxia with Coenzyme Q10 deficiency is another rare recessively inherited ataxia which can be caused by mutations in a number of genes involved in the biosynthesis of ubiquinone (CoQ10). CoQ10 levels can be measured on muscle biopsy and on blood samples and if they are significantly reduced then supplementation with CoQ10 can be an effective treatment (see section Ataxia with CoQ10).

For more information on specific dietary interventions see section Treatable ataxias. Further dietary advice is also found within other subsections of this page, as some symptoms require dietary changes.

Excess salivation is a common and distressing problem for patients with ataxia, especially in later stages. Saliva that remains pooled in the mouth may become an aspiration source and thus could result in choking and pneumonia98. On a psychological level it is very distressing to patients who find themselves dribbling and is often quoted by patients as a major factor in withdrawing from social situations98. Patients sometimes get skin lesions from prolonged dribbling at night when they are lying on their side and this can also be embarrassing and distressing for them.

Sometimes patients experience a thick secretion rather than excessive production of saliva. It is important to evaluate the type of secretion as that informs the treatment (see table 11). Sialorrhea is normally associated with dysphagia, thus a referral to a speech and language therapist is recommended for assessment of swallow (see section Speech and language therapy).

Table 11: Summary of treatments to be considered

(listed in the order that the treatments are often trialed)

| Excessive thin secretion | Thick secretion |

|

Postural changes Support collars Natural products: sage (capsules, tea tinctures), dark grape juice Medications: Transdermal hyoscine (scopaderm) Amitriptyline Atropine 0.5% drops sublingual Benztropine Glycopyrrolate Benzhexol Botulinum toxin injections Manually assisted cough technique |

Ensure adequate hydration (2L/day) Avoid mucus thickening foods (dairy) Avoid caffeinated drinks and alcohol Suck sweets to stimulate saliva production Steam inhalation/humidifiers/nebulisers Pineapple puree/juice |

The table is adapted from Bavikatte et al 201299

| Recommendations | Grade | |

|

1. |

Sialorrhea is normally associated with dysphagia, thus a referral to a speech and language therapist is recommended for assessment of swallow. |

GPP |

|

2. |

Treat sialorrhea and thick secretions according to the treatment pathway in table 11. |

GPP |

Problems

Hearing loss is a known symptom of the progressive ataxias. It is common in Friedreich’s ataxia100 and those ataxias involving peripheral neuropathies. It is therefore important that when an ataxia is diagnosed and there is a hearing problem that the patient is referred for Audiology testing, in order to establish the nature of the hearing loss, establish hearing thresholds and functional abilities (i.e. speech perception). Routine monitoring should be put in place.

Assessment

The assessment of the ataxic patient can be challenging, and it is important to consider the possibility of Auditory Neuropathy Spectrum Disorder (ANSD), which is a known manifestation in conditions such as Friedreich’s ataxia101 and has recently been shown to be a feature of the spinocerebellar ataxias too102.

A typical assessment should include pure tone audiometry using both air conduction and bone conduction, tympanometry, otoacoustic emissions and acoustic reflex testing. Most importantly, in this clinical population, functional assessments such as speech testing, both in quiet and in noise, should be undertaken103.

Discrepancy between hearing thresholds and speech perception is indicative of ANSD and objective testing such as auditory brainstem response, and in case the otoacoustic emissions are absent, cochlear microphonic are necessary to confirm the diagnosis of ANSD104. Cortical auditory evoked potentials testing is also recommended. Referral to otorhinolaryngology should be made where appropriate.

Management

In case of ANSD, hearing aids are often unsuitable105, but a hearing aid trial should be considered. Other assistive devices, such as FM hearing devices, have been shown to be of benefit in Friedreich’s ataxia100,106 and spinocerebellar ataxias102 and results of further trials are awaited. At the time of writing these devices are not available routinely in the UK although they are in other countries eg: in Australia people with ataxia are offered FM hearing devices, such as the Roger pen system, as part of the National Health service. Dexterity may be an issue, and therefore appropriate devices should be chosen.

For those who do not achieve any benefit from appropriate aiding with hearing aids, it is appropriate to refer for further assessment to the local cochlear implant centre. Mild improvement was seen in a small study of non-ataxic patients with ANSD with a cochlear implant even if the hearing thresholds do not meet NICE TAG 166 criteria (profound at 2 and 4 kHz bilaterally).107

Where possible, referral to hearing therapist or speech and language therapist should be made upon diagnosis of a hearing loss (See also section Speech and language therapy). Hearing therapists can offer guidance in communication tactics, hearing aid management and advice on assistive listening devices to help both at work and in the home.

| Recommendations | Grade | |

|

1. |

If a patient is experiencing hearing problems refer to Audiology services for a battery of hearing tests. |

GPP |

|

2. |

A hearing aid trial should be considered although it is often not suitable for this patient population. |

GPP |

|

3. |

A trial with an FM hearing device is recommended in cases of ataxia with ANSD. |

C |

|

4. |

Refer to hearing therapist or speech and language therapist for guidance on communication tactics. |

GPP |

|

5. |

For those who do not achieve any benefit from hearing aids, consider to a cochlear implant centre. |

D |

|

6. |

In specific cases (eg: ADNS) a referral to a neuro-otologist should be considered. |

GPP |

Many of the ataxias are associated with eyes symptoms such as oscillopsia due to nystagmus, diplopia or reduced vision. A referral to a neuro-ophthalmologist is recommended if eye symptoms are present.

Nystagmus

Nystagmus can be a symptom experienced by patients with ataxias and it can sometimes also cause oscillopsia (a disabling subjective sensation of movement of the visual world). These involuntary eye movements do not require treatment if patients are not affected, however therapy should be considered when visual disability is present. There have been a few randomised placebo-controlled treatment trials; these have shown the efficacy of gabapentin in treating symptomatic pendular or gaze-evoked jerk nystagmus108,109 and sometimes downbeat nystagmus109. Downbeat nystagmus can also be treated with 3,4-diaminopyridine and baclofen109,110. A number of other studies (non-randomised controlled trials) have shown the efficacy of other medications such as clonazepam and valproate for pendular nystagmus and of 4-aminopyridine for downbeat nystagmus111.Orbital injections of botulinum toxin to weaken the extraocular muscles have also been reported to be beneficial in some patients, although there are limitations to this approach (discussed in a review in 2002)112.

Diplopia

Diplopia (seeing ‘double’) is not a common symptom associated with the ataxias but may occur. The images are usually separated horizontally (rather than vertically), as a result of a manifest exo - or eso deviation of the visual axes, and is concomitant in all directions of gaze. Single vision can be restored optically using prisms, so eye muscle surgery is rarely necessary.

Visual impairment

Degeneration within the retina or optic nerves is well recognised in association with several of the ataxias. For example, approximately half of patients with Friedreich’s ataxia have clinically apparent optic atrophy, although patients may not be aware they have subnormal vision and severe visual loss is uncommon113,114. Progressive deterioration in visual acuity is often seen in patients with SCA7 because of bilateral (and usually symmetrical) maculopathy.

At this stage there is still no known treatment either to prevent or to treat the retinal or optic nerve manifestations of ataxic disorders. However, patients can benefit from a wide range of low vision aids as well as having their visual disability registered.

| Recommendations | Grade | |

|

1. |

A referral to a neuro-ophthalmologist is recommended if ataxia patients have any eye symptoms. |

GPP |

|

2. |

If disabling nystagmus or oscillopsia is present treatment is recommended, often with either gabapentin or baclofen. |

B |

|

3. |

Refer to an optometrist or neuro-ophthalmologist for restoration of single vision with prisms in cases of diplopia. |

GPP |

|

4. |

Patients with visual impairment should be offered low vision aids and the possibility of having their visual disability registered. |

GPP |

There is emerging research to suggest that patients with ataxia are at risk of cognitive impairment, as with most patients with other neurological conditions. However, relatively little research has been conducted so far in trying to determine the specific cognitive impairments in ataxia. Ataxia is a symptom of a number of conditions, and it may be possible that the different genetic mutations as well as the extent of degeneration underlying the different conditions may lead to different patterns of deficits.

Research in Friedreich’s ataxia and various different types of spinocerebellar ataxia suggest some impairments in executive skills15,115–127, attention115–117,126,127, memory119,122–124,126,128,129, speed of information processing120,121,124,127,128,130,131 and, possibly only in some types of spinocerebellar ataxia, social cognition115,116,132. In this instance, social cognition refers both to ‘Theory of Mind’ skills, which is the ability to attribute mental states to others and understand that the beliefs and knowledge of others may be different from your own115,116, as well as to the ability to recognize different emotions in others133. There is a lack of homogeneity within the conditions; thus, patients with certain subtypes of spinocerebellar ataxia may be more impaired cognitively115,116.

The delineation of a patient’s cognitive strengths and weaknesses is important for the management of their condition, and forms the basis for which recommendations of rehabilitation strategies can be made. Even mild impairments can have a significant impact upon a patient’s daily function at home and at work, and thus patients can benefit from cognitive rehabilitation, as demonstrated in patients with Friedreich’s ataxia132.

To identify cognitive symptoms one needs to administer a detailed and comprehensive neuropsychological evaluation. Thus, referral to a Neuropsychology Department is recommended. Neuropsychological evaluation can not only screen for cognitive impairment occurring in the different types of ataxia, but can also monitor the progression of any such impairment over time. One study has tracked the longitudinal course of cognitive impairment in patients with ataxia121, but there is generally lack of research in this area. Characterising the course of the impairment is of paramount importance to inform the likely prognosis.

| Recommendations | Grade | |

|

1. |

When cognitive impairment is suspected (even if mild) referral to a Neuropsychology department is recommended. |

GPP |

|

2. |

Cognitive rehabilitation is recommended for those patients with cognitive impairment. |

C |

|

3. |

Characterising the course of the cognitive impairment is advisable in order to inform the likely prognosis. |

GPP |

Patients with ataxia, as those with other neurological conditions, are susceptible to depression134,135. Practical and effective treatment of symptoms of depression can be carried out in primary care, without the need for specialist psychiatric input. In addition to pharmacological interventions, psychological and psychosocial interventions including counselling and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) can offer significant benefits. In some cases, more input from secondary level psychiatric services may be indicated, especially if depression is severe, there is a significant risk of self harm or the depression has not responded to an adequate course of antidepressant medication. Although there is a lack of evidence for treatment and management of depression specifically in patients with ataxia, NICE have produced Guidelines for the treatment and management of depression in adults with a chronic physical disorder including neurological disorders, and it is recommended these should be followed136.

Dementia or psychosis are less common in patients with ataxia. These can normally be managed in primary care. However, depending on severity and risk the patient may require input from specialist psychiatric services. Again there is a lack of evidence into the treatment and management of these symptoms specifically in patients with ataxia.

| Recommendations | Grade | |

|

1. |

In many cases depression can be treated in primary care using medications, counselling or cognitive behavioural therapy. |

GPP |

|

2. |

In more severe or complex cases of depression and other psychiatric symptoms a referral to a psychiatrist/neuropsychiatrist in secondary care is recommended. |

GPP |

|

3. |

For adults consult NICE Guidelines for the treatment of depression in patients with a chronic physical disorder136. |

GPP |

Some patients experience ‘episodes’ of ataxia and may be diagnosed with an inherited episodic ataxia. Episodic ataxia type 1 and 2 (EA1 and EA2 respectively) are the best characterized genetically and the most well-known, but other rarer forms (constituting EA3 to EA8) have been identified in single kindreds and associated with mutations in known genes and/or linked to potential genetic loci137.

The most common form is EA2 in which patients present with attacks of cerebellar dysfunction lasting hours to several days, and can be associated with other neurological features such as hemiplegic migraine, migraine with or without aura and epilepsy, all of which merit treatment in their own right. A second stage may develop later in the life in which the condition becomes progressive138. Triggers should be identified and avoided, including stress, caffeine and alcohol consumption. Attacks can be precipitated by exertion. However, regular but modest exercise should be encouraged138.

Acetazolamide, a sulfa-containing carbonic-anhydrase inhibitor, is used as a first line drug for the prevention or reduction in frequency of episodic ataxia attacks. It has been used effectively in clinical practice for many years, but because of the rarity of the condition there have been no randomized–controlled trials, and its mechanism of action is unknown. Long-term use of acetazolamide is associated with dose-related side effects, such as renal calculi, gastrointestinal symptoms, paraesthesiae, fasciculations and fatigue.

Patients should be advised to keep hydrated to prevent the development of renal calculi and should undergo annual ultrasound screening of the urinary tract. Antibiotic sulfonamides are well known to cause types 1-4 hypersensitivity reactions, but a recent case series has shown there to be little suggestion of cross-reactivity between antibiotic and non-antibiotic sulfonamides139. A history of previous hypersensitivity reaction secondary to sulfonamides is, therefore, not an absolute contraindication but acetazolamide should be used with caution and under surveillance.

Although acetazolamide is the standard treatment for episodic ataxia type 2, some clinicians used to use dichlorphenamide (another carbonic-anhydrase inhibitor, no longer available in the UK), which has a beneficial effect in periodic paralyses but no randomized-controlled trials exist for its use in episodic ataxia140. 4-aminopyridine is a potassium channel blocker used in patients with episodic ataxia and nystagmus, and has been shown to reduce the frequency of attacks and improve patient reported quality of life141. At the time of press this medication is not licensed for use in episodic ataxia in the UK, but may be available on a named patient basis.

Episodic ataxia type 1 is characterized by constant myokymia, neuromyotonia, and dramatic episodes of spastic contractions of the skeletal muscles of the head, arms, and legs with loss of both motor coordination and balance. The episodes are brief, typically lasting seconds. The management of EA1 is centred around symptom prevention by avoidance of known triggers, as in EA2137. Frequent attacks may be controlled with acetazolamide although there is some variation on the efficacy between individuals137. Case studies and other small studies suggest that the frequency and severity of attacks may be controlled by anti-epileptic medications such as carbamazepine, phenytoin or lamotrigine, but again there is variable response between individuals137,142.

| Recommendations | Grade | |

|

1. |

Advise episodic ataxia patients on identification and avoidance of common triggers that may cause attacks such as stress, caffeine and alcohol consumption, and excessive physical exertion. |

GPP |

|

2. |

Acetozolamide is recommended as the first line drug in episodic ataxia types 1 and 2, although not all patients respond. |

GPP |

|

3. |

Patients taking acetazolamide should be advised to keep hydrated to prevent the development of renal calculi and should undergo annual ultrasound screening of the urinary tract. |

D |

|

4. |

Patients with a known hypersensitivity to sulponamides should be counselled at the start of treatment and need to be kept under surveillance. |

GPP |

|

5. |

Consider use of 4-aminopyridine on a named patient basis as second line drug in EA2 if acetazolamide is not beneficial. |

C |

|

6. |

In EA1 consider use of carbamazepine, phenytoin or lamotrigine as second line treatment. |

GPP |

This information is taken from Management of the ataxias - towards best clinical practice third edition, July 2016. This document aims to provide recommendations for healthcare professionals on the diagnosis and management of people with progressive ataxia. To view the full document, including references, click here.

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

LATEST NEWS

- All

- Cerebellar ataxia

- Friedreich's ataxia

- Research News

- SCAs

- Your Blog